By Dr. Harold D. Hunter

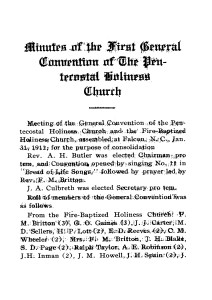

The historic achievement of unity made visible on January 31, 1911 writes plainly the message that much Pentecostal theology has been done in the context of prayer and worship. It is this matrix that caused two churches to realize a common mission and vision. The older, larger church was the Fire-Baptized Holiness Church (FBHC) but a secure anchor was found in the Pentecostal Holiness Church (PHC). The group at the merger was small but their vision was big as they sensed a calling to propel the emerging church to far flung parts of the world.

These saints imbibed a spirituality of the cross. They continually talked about being living sacrifices crucified unto Christ and lived that out through constant prayer, fasting, covenant-keeping and non-stop church attendance. Their discipline and spirituality were not particularly unusual in the early 20th century and not exclusively owned by any particular group of Christians in the Global North.

Pandita Ramabai, an Indian social reformer and Christian, who promoted deliverance of women from child marriages and education for women in India.

With the fresh winds of the Spirit came the Pentecostal message with its empowering and liberating message of the resurrection. Some of these theological themes coalesce in J.H. King’s 1914 Passover to Pentecost. King wrote this influential thesis in Memphis after returning to the U.S.A. from Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. At the time of the merger, King was in India making connections important to global Pentecostalism through the likes of Pandita Ramabai at the Mukti Orphanage with direct ties to a future IPHC affiliate, the Pentecostal Methodist Church of Chile.

Early Pentecostals had a passion for their faith that thought little about much of anything other than singing, praying, preaching, agonizing, confessing, seeking the anointing, testifying, studying and memorizing the Bible, taking light to dark places, and the like that in some cases didn’t even require a brush arbor. These early Pentecostals faced threats by people with guns, knives, fire, hangings, poison, whips, brute force, etc., yet they were quite literal about bringing in the “poor, the crippled, the blind and the lame” (Luke 14:21, NRSV) as well as going “out into the roads and the country lanes and compel people to come in, so that my house may be filled” (Luke 14:23, NRSV).

Those who surrender to the postmodern paradigm of post-denominationalism and care little about pre-denominational churches (Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox) should read the commentary on John 17:21 by J.H. King and G.F. Taylor. North Carolina Conference Superintendent A.H. Butler would call on this text during the November 21-23, 1911 PHC North Carolina convention as he looked back at recent events. The January 31, 1911 merger of the FBHC and PHC was the first instance of organic unity achieved by Classical Pentecostals in the U.S.A.

The FBHC and PHC were Holiness churches who adopted the Azusa Street message due in no small part through PHC G.B. Cashwell’s 1907 revival in Dunn, North Carolina. Both groups were avid readers of J.M. Pike’s The Way of Faith and W.J. Seymour’s The Apostolic Faith. The parade of those who went to the Azusa St. Revival in Los Angeles, California included Daniel Awrey (FBHC), G.B. Cashwell (PHC), T.J. McIntosh (PHC), Anna Deane, F.B. Britton (FBHC), S.D. Page (FBHC), A.G. Canada (PHC), and K.E.M. Spooner. National conventions of these churches officially codified this Pentecostal experience by changing their doctrinal statements to defend initial-evidence Spirit baptism.

Although the PHC and FBHC ordained women ministers prior to the Pentecostal infusion in 1906, the only women present at the merger were from the FBHC which is consistent with their constitution. According to the printed minutes from 1911, these FBHC women were delegates who voted in business sessions. FBHC Ruling Elders [Conference Superintendents] were male and female, black and white including at least one African-American woman. The final issue of Live Coals of Fire (June 1900) showed 140 full time evangelists scattered over twenty-three states or territories and in two Canadian provinces. B.H. Irwin, the founder of the FBHC, reached native peoples and immigrants from Europe, Africa, and Latin America and later sought to minister in Asia.

Before leaving for his tour around the world launched in late 1910, J.H. King got favorable votes for the merger from seven FBHC conventions and each convention was represented at the merger in Falcon by a ruling elder. These FBHC ruling elders came from North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, Florida, Tennessee, and Oklahoma.

G.F. Taylor would later write that the most contentious issue that almost derailed the merger was the question of divorce and remarriage. As Taylor pointed out, it was the PHC who had previously adopted restrictive legislation on this issue. Another pitfall was the question of outward adornment and while not unique to these groups tension surfaced in the effort to apply strict rules for men as well as women. While this was not truly egalitarian, the FBHC posture was less sexist than some other groups and not unlike what J.H. King found when in 1912 he preached to Narvaitic Lestadian Lutherans in Finland. When hearing about the dietary restrictions imposed by the FBHC but also respected by the PHC, we do well to put them in context as a people who had a less selective reading of Leviticus. Modern Pentecostals who have forgotten Leviticus may find it difficult to confront 21st century moral issues without this much maligned book of the canon.

J.H. King while General Overseer of the FBHC adopted the Azusa St. message as a result of a revival at his Toccoa congregation led by G.B. Cashwell. When Cashwell started Bridgegroom’s Messenger in 1907 the corresponding editors were G.F. Taylor and A.H. Butler. A frequent and important contributor was J.H. King at a time when the PHC considered Cashwell’s magazine their quasi-official organ.

One would do well not to understimate the role of J.A. Culbreth. Culbreth, a legendary layperson for the PHC, built an Octagon Tabernacle in Falcon, North Carolina. Culbreth started independent annual camp meetings in Falcon in 1900 that required huge canvas tents and also established the Falcon Holiness School then an orphanage. At the time of the merger, there were residences in Falcon for J.A. Culbreth, G.F. Taylor, A.H. Butler, J.H. King S.D. Page, F.M. Britton, and A.E. Robinson.

J.H. King was the invited speaker for the 1907 Falcon Camp Meeting and he returned as speaker for the 1908 Falcon Camp Meeting. King then determined to move to Falcon where he taught at the Falcon Holiness School and took charge of what became the orphanage. All this transpired while King remained general overseer of the FBHC.

When the FBHC was between the publication of Live Coals of Fire and Live Coals, they used PHC founder A.B. Crumpler’s Holiness Advocate. J.H. King wrote the foreword to G.F. Taylor’s Spirit and the Bride that was released in 1908. Taylor became principal of the Falcon Holiness School in 1907. He also is the first recorded pastor of the PHC at Falcon. The Falcon Publishing Company started by J.H. King in 1909 published The Apostolic Evangel edited first by King then J.A. Culbreth and eventually A.E. Robinson.

Talks about consolidation gained momentum in 1910 and the joint committee to move things forward included G.F. Taylor, F.M. Britton (then acting General Overseer of the FBHC), and J.A. Culbreth. Among those in the PHC advocating the merger at the time were G.F. Taylor, A.H. Butler, A.G. Canada, and C.B. Strickland.

In April 1910, representatives from the PHC and FBHC met in Falcon for two days to tackle the thorny issues and did so in full view of “spectators”. The FBHC discipline came under close scrutiny, but after a day and a half consensus was achieved. The official delegates meeting in January 1911 easily adopted the proposed new discipline by a vote of 36 to 2. The “Basis of Union” in the 1911 Constitution and General Rules of the Pentecostal Holiness Church was heavily indebted to FBHC documents. The discipline proposed by the joint committee and adopted by the merged church was taken from the Donaldson, Georgia Holiness Church discipline (c. 1897) with minor editing by A.B. Crumpler.

The form of government that emerged incorporated congregational and presbyterian elements whereas the FBHC had been rigidly episcopal and Crumpler had expected strict compliance in his days as head of the PHC. A new chapter was opened when they put into practice the famous dictum from Count Nicolaus Ludwig Zinzendorf used by Crumpler in the 1902 Holiness Advocate: “Our principles are: In essentials, unity; in non-essentials, liberty; in all things, charity, and are bound to commend themselves to every broad-minded Christian in the world who believes in Christian liberty”.

It is evident that prayer was an integral part of the actual merger realized at Falcon in 1911. The Minutes of the First General Convention of the Pentecostal Holiness Church mention prayer throughout the proceedings. These prayers should not be taken as mere formalities to fill out an agenda, but it would be best to see here impassioned pleas for divine guidance.

While the Falcon camp meetings provided an important time for the groups to worship together each year, ample evidence abounds that these were people who knew how to travail, pray with passion, routinely hold `protracted services’, etc. until their human desires and wills were broken and they were open to the leading of the Holy Spirit. Specific references of this sort about Falcon camp meetings may be found in periodicals of the time like the Holiness Advocate and the Apostolic Evangel.

Just prior to the actual merger on January 31, 1911, A.G. Canada held a revival in Falcon attended by many of the major players in the final outcome. As Joseph Campbell comments, “The spiritual preparation which resulted from these services no doubt played a large part in bringing about the consolidation.”

When the camera in outerspace looks down at planet earth spinning in the universe, one can quickly be reminded that we are surrounded by a ‘great cloud of witnesses’ who will encourage us to ‘run the race’ while ‘fixing our eyes on Jesus’ (Hebrews 12:1, 2).