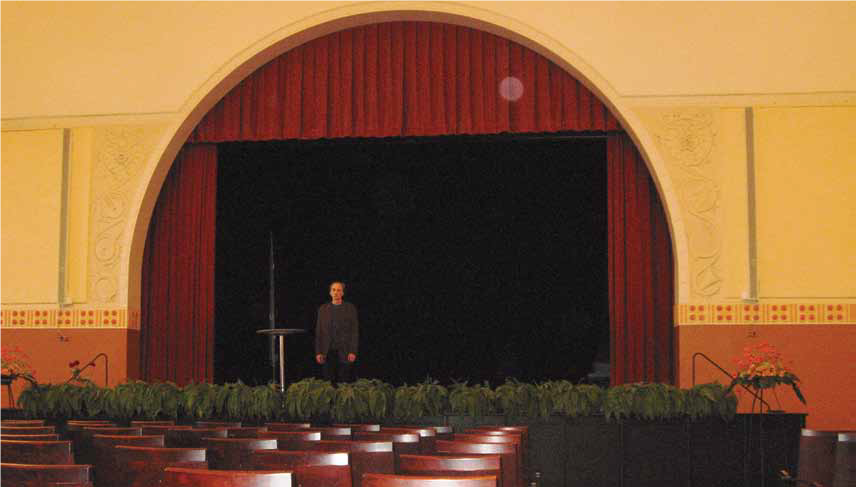

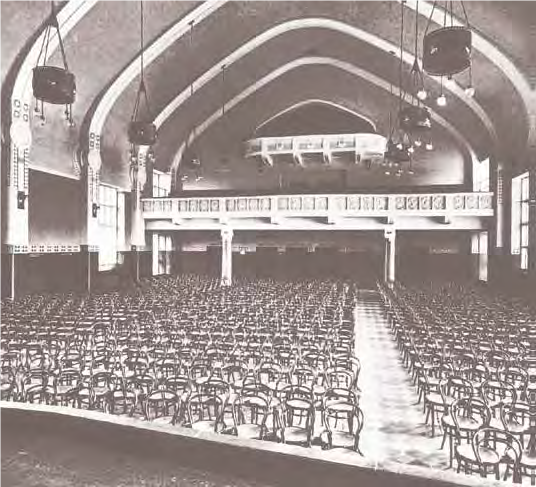

Dr. Harold D. Hunter on platform of Workers’ Hall. J.H. King preached here in 1912 to a capacity crowd of 1,000. After being bombed in WWII, the complex was rebuilt and is now known as the Helsinki Congress Paasitorini (see http://paasitorini.fi/en/).

I had the privilege in January of 2009 to visit a parish in which the legendary J. H. King made history in June 1912. I was hosted by Dr. Gavin Wakefield, professor at the University of Durham, who has released two books on Rev. Alexander Boddy.1 The meeting King attended in 1912 was held at Boddy’s Anglican Church in Sunderland, England.

Rev. Boddy gave a vivid account of the meeting in question in his famous magazine known simply as Confidence. It is also from the pages of Confidence that we learn more about Bishop King and the impact he had on European Pentecostal leaders. Let us walk in King’s footsteps as we watch him solidify his celebrated place in history.

Let’s step back to where vision was transformed into a milestone in King’s illustrious ministry. J. H. King

was in Falcon, North Carolina, in 1909 when his close associate A. E. Robinson implored him to come to Columbia, South Carolina. At first, Robinson did not expose his motive, and King replied that heavy responsibilities and lack of travel funds made the trip impossible. Robinson then told him that Mr. and Mrs. A. G. Garr, who were well-known Pentecostal missionaries to China, were holding services at the Oliver Gospel Mission and that King’s travel expenses would be covered.

Much ink has been spilled retelling the amazing story of A. G. Garr and his wife, but this is beyond the scope of our narrative. A short version centers on a remarkable turn from a group

that battered the Azusa Street Revival to becoming one of the revival’s leading lights, particularly in Asia but also in parts of the southeastern United States. Even before meeting King in person, they had a “conviction” that he should visit Pentecostal centers outside the U.S.

Once King arrived in Columbia, SC, in May 1909, the Garrs and Robinson made their case to him. His response was that he could not simply walk away from the young orphanage he had help open in Falcon or the recently launched periodical the Apostolic Evangel. Yet King grew increasingly preoccupied with this notion and described it as “a burden so heavy that I could scarcely bear it.”2

King went on to tell of divine intervention during the December 31, 1909, Watch Night service in

Falcon. When the service was over, King’s “call” to undertake a world tour was sealed. But this was not the

last chapter, for when King left the Falcon Holiness School in January 1910, he received confirmation of his world mission tour while at Texas Holiness University. He wrote in The Bridegroom’s Messenger:

God clearly and miraculously opened the way for me to go with Brother Britton to Greenville, Texas…. While there God gave me a message in tongues and the full interpretation to the effect that I should leave, or begin to make preparation to leave in the spring.3

With missionaries in tow, King left San Francisco in September 1910. Much has been made about King’s many accomplishments in Asia, but neither these exploits nor the memorable visit to Jerusalem, Palestine, will be recounted here. We will move along quickly toward the end of his two-year tour when he made his mark on the fledgling Pentecostal Movement in Europe.4

During his months of travel across Europe, King would go to Switzerland, England, Holland, Norway, Denmark, Finland, and Scotland, while passing through Italy, Germany, and Sweden. The launching pad for his most influential work in Europe started with the historic conference in Sunderland, located in northeast England.

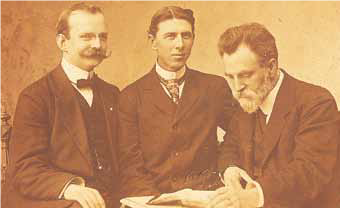

J. H. King (center) with Barratt, founder of European Pentecostals, to his right and Barratt’s assistant, Rev. Anderson, in Oslo, Norway.

Yet it must be noted that King cemented a firm relationship with T. B. Barratt of Norway, who late in

1906 introduced the message from the Azusa Street Revival to Europe. King not only corresponded with Barratt; he visited him twice in Christiania (Oslo).

And to get a flavor of his other stops, consider his preaching in Helsinki, Finland. Here King would link up with a Lutheran Revival Movement and preach to a group called the Narvaitic Lestadians, who had experienced an outbreak of speaking in tongues, prophecy, and healing 50 years prior to the Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles, California. Even prior to this in Finland was the Savonjävi outpouring with tongues-speech and the like in 1796. King’s meetings were moved to the largest auditorium in Helsinki, and, with Gerhard Smith, he consecrated the first of many Pentecostal missionaries from Finland.5

A look inside the Workers’ Hall in Helsinki in 1908, with smaller chairs than used today. (Image scanned from brochure identified as Helsinki Auditorium)

A reporter for the Lutheran church magazine Kotimma (8 July 1912) praised King’s preaching and said that it was sound. The reporter was pleased that King spoke about mistakes and biases that had taken place in many Pentecostal meetings around the world as some practitioners abused the privilege of their claim to a baptism in the Holy Spirit. “There are many who fancy that they have received Spirit baptism even though they had not yet become conscious of their own sinfulness and do not know anything about the biblical awakening and cleansing of their conscience.”

The reporter went on to say he was encouraged to know that among leaders of the Pentecostal Movement were “open-minded men as pastor King” (Kotimaa, 10 July 1912).

Our sojourn with J. H. King in Europe has taken us to what he called “The Land of a Thousand Lakes,” many of which he discovered while preaching at Tampere and traveling over to Turku, Finland. For now, let us return to Helsinki for a prayer meeting held during the early summer 1912 at the Fire Brigade Hall with both T. B. Barratt and J. H. King present.

A prayer meeting for believers was announced [for] 8 o’clock in the morning. All were assembled for quiet and voiceless prayer. This time there was no reading, no singing, but everyone worshipped quietly before the Lord. About 11-12 o’clock at noon a strong humming was heard, like a whole big crowd of worshippers had stood up and gone out of the room. At that moment I lifted my head and wondered if worshippers had gone away already. However nobody had come in and the Holy Spirit had filled the room where we were worshipping.

Consequences were seen immediately: people got up under the power, some asked us to pray for their sicknesses, and nine seekers received Spirit baptism. Signs followed those who believed.6

Rev. A. A. Boddy, vicar of All Saints’ Church in Sunderland, sponsored his fifth Whitsuntide Conference, which always attracted prominent Pentecostal leaders in Europe and attempted to bring unity to the Pentecostal Movement whilst being sensitive to the best course for these diverse groups to endorse. These meetings were made of no small importance due to notices then reports in Boddy’s widely read paper, known simply as Confidence, which was first published in 1908.

As the body gathered for the meeting in May 1912, J. H. King was not simply counted among their number but was an honored guest and keynote speaker. And of no little consequence was his signing of a document forged by the newly organized International Pentecostal Council (1912-1914).

Although this group had been foreshadowed in the 1908-1911 Leaders’ Meetings and came to an untimely end with the advent of World War I, it is nonetheless seen as having laid the foundation for what today is known as the Pentecostal World Fellowship (PWF).7 The PWF finally got its start in Switzerland in 1947 and was once led by IPHC Presiding Bishop James D. Leggett. Currently, IPHC Presiding Bishop Beacham is Secretary of the PWF.

Ironically, Boddy also published an “Important Pentecostal Manifesto” drawn up at the Pentecostal Camp Meeting held June 1908 at Alliance, Ohio. One of the signatories of this unusual document that formed the ecumenical body named The Apostolic Faith Association was J. H. King.8

King, being the only Pentecostal leader present from North America at Sunderland in 1912, illustrates the commitment of the PHC to break new ground by celebrating calls for unity in a movement that has been too often known for its fragmentation. Yet even when compared to the mainstream form of ecumenism that first wrote of “visible unity” at a world conference in 1927—also in Switzerland—the IPHC had anticipated this need years earlier when in 1911 the Fire-Baptized Holiness Church merged with the Pentecostal Holiness Church to create what is now known as the IPHC Ministries. The centennial of this monumental event was an excellent time to reflect on the precedent established by the IPHC in 1911.

J. H. King’s relationship with these European Pentecostal leaders did not end with his tour of preaching, teaching, networking, sharing, and listening. In particular, Boddy and King respected each other and formed a close bond. In early August 1912, they sailed together to the United States, thus bringing an end to King’s world tour. Boddy would not only write about King and publish an article by him, but Professor Gavin Wakefield—the esteemed biographer of Boddy— said Boddy often looked to King for leadership when dealing with various factions of the emerging Pentecostal Movement in the United States. Boddy himself put it this way after renewing their friendship in 1914 at the Atlanta Camp Meeting: “There is no one with a truer heart in Pentecostal circles [than J. H. King].”9

Dr. Harold D. Hunter is director of the Archives and Research for the IPHC.

ENDNOTES:

1 See Gavin Wakefield, Alexander Boddy: Pentecostal Anglican Pioneer (London: Paternoster Press, 2007). Former Fire-Baptized Holiness Ruling Elder Daniel Awrey spoke at the Sunderland conference in 1909 (p. 120).

2 J. H. King and Blanche L. King, Yet Speaketh: Memoirs of the Late Bishop Joseph H. King (Franklin Springs, GA: Publishing House of the Pentecostal Holiness Church, 1949), p. 143.

3 J. H. King, “Unfolding of His Purpose,” Bridegroom’s Messenger 3:56 (February 15, 1910), p. 2.

4 A good starter on the early missionary enterprises may be found in G. F. Taylor, “Our Church History. Chapter XI: Foreign Missions,” The Pentecostal Holiness Advocate 4:49 (April 7, 1921), pp. 8-10.

5 Much useful information about King’s visit to Finland was provided through e-mail from and conversations with Jouko Ruohomäki (10-11/2008), who drew on the monthly magazines Toivon Tähti, Kotimaa, Ristin, Voitto, and Pekka Brofeldt’s memoirs Helluntaiherätys Suomessa. Cf. See Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen, “The Pentecostal Movement in Finland,” Journal of the European Pentecostal Theological Association 23 (2003), p. 118.

6 Translated (10/2008) by Jouko Ruohomäki from Pekka Brofeldt, Helluntaiherätys Suomessa, 1932, pp. 36, 37.

7 “Consultative International Pentecostal Council,” Confidence 5:6 (June 1912), pp. 133, 144. Cf. Cornelis van der Laan, “The Proceedings of the Leaders’ Meetings (1908-1911) and of the International Pentecostal Council (1912- 1914), Pneuma: The Journal of the Society for Pentecostal Studies 19:1 (Spring 1988), pp. 36-49; Cecil M. Robeck, “Pentecostal World Conference” in New International Dictionary of the Pentecostal-Charismatic Movement, ed. by Stanley M. Burgess (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2002), p. 972.

8 “Important Pentecostal Manifesto,” Confidence #5 (August 15, 1908), p. 9f;”The Pentecostal Mission Union,” Bridegroom’s Messenger 2:43 (August 1, 1909), p. 1.

9 Confidence (September 1914), p. 13.

The article above originally appeared in the IPHC Experience magazine in April 2009 and June/July 2009 as two articles.