Bishop Doug Beacham shared Remembering for the Future after the 2011 Centennial in Falcon, North Carolina. For the full text, simply click the link.

Below are two chapters from this book that share the early history of the IPHC (shared with permission):

Two Streams Merge

This year [2011] we gather from around the globe to celebrate and affirm the Second Jubilee of the International Pentecostal Holiness Church. One hundred years ago the Holy Spirit led two Wesleyan-influenced holiness groups, both transformed by the Azusa Street Pentecostal experience, to unite in order to proclaim more effectively the gospel of Jesus Christ.

The centennial celebration was not merely a recitation of history. It was remembrance for the sake of the future. We were and are keenly aware of the thousands of named and unnamed persons who have served Jesus Christ around the world through this tribe of His kingdom, the International Pentecostal Holiness Church. We gathered to see a compelling reenactment of the merger event one hundred years earlier. Through inspired actors, we heard the voices of S.D. Page (the first General Superintendent of the new movement), George F. Taylor, Joseph H. King, and others.

The Wesleyan Holiness Background

The document begins by affirming the historical connection of the two Wesleyan-influenced holiness groups: The Fire-Baptized Holiness Church and the Holiness Church of North Carolina. The perspective of time allows us to see the various ways the Holy Spirit shaped both movements in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Through various camp meetings, especially the inter- denominational Falcon Holiness Camp Meeting, leaders of these movements ministered with one another, finding shared theology and understandings of the Christian life.4

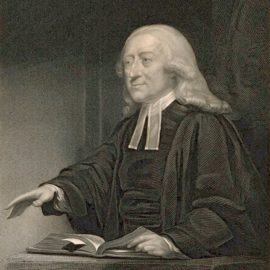

It is significant that the IPHC’s theological roots are connected to the holiness teachings of Reverend John Wesley (1703-1791), an Anglican minister and the founder of Methodism. Reared in the home of his Anglican priest father, Wesley was influenced by both parents, but especially by his mother, Susanna. A graduate of Christ Church, Oxford University in England, John and his brother Charles felt a burning desire for a closer walk with Jesus Christ. Their commitment to serve Christ led them to form the “Holy Club” at Oxford, where they were ridiculed for their “methods.” Their “Methodism” became a renewal movement within the Church of England.

John Wesley felt a call to do missionary work in the American colonies and came to Savannah, Georgia, to serve. The sea journey from England to America brought him face to face with his fears and insecurities about his own salvation. Aboard the ship were German Moravians, followers of Count Zinzendorf. During storms at sea, Wesley was impressed by the Moravians’ peace with God. They experienced a serenity and intimacy with God that Wesley did not have. His experience as a missionary in Georgia did not aid his search for such an experience. Wesley lamented in his journal, “I came to convert the Indians, but who will convert me?”

Upon returning to England in December 1737, Wesley was at a low point spiritually. At the insistence of his brother Charles, he attended a Moravian prayer service on Aldersgate Street in London on the night of May 24, 1738.

John Wesley. Engraving by J. Thomson after J. Jackson. Credit: Welcome Collection.

Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Listening to a reading of Martin Luther’s Preface to the Epistle to the Romans, Wesley heard the reality of gospel grace. He described that night in these words, “About a quarter before nine, while he [Luther] was describing the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ, I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation, and an assurance was given me that he had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death.”

That night began a process of transformation in John Wesley’s life. As an Anglican priest, Wesley had found himself serving God to earn God’s favor. Now, he began a fresh journey of faith with the foundation of salvation by faith in what has been done in Christ alone. From that knowledge Wesley began to understand that a holy life is not attained by our own efforts but by the continued workings of God’s grace, a grace planted in our hearts when we are “born again.” But that grace was also sufficient to deal with our sinful, fallen nature, which every person has inherited from Adam’s fall (Genesis 3). Wesley taught that sanctification is the victory of grace over the “old person.” Sanctification makes one a “new person in Christ,” conformed to the holy image of Jesus.

The IPHC has experienced this connection to John Wesley in a number of ways. First, the IPHC began as two movements in the late 1890s informed by Wesley’s concept of personal holiness. Second, one of our cardinal doctrines is sanctification that is a second, definite work of grace. Third, from Scripture and Wesley we believe that the Christian life can be lived with present victory over sin. Fourth, like Wesley and the Methodists after him, the IPHC is Arminian in terms of how we see God’s seeking the lost. Fifth, many of our early leaders were discipled in Methodist congregations. Sixth, the core of our theology and church government reflect the Wesleyan, Anglican tradition.

The 1906 Pentecostal Revival

In addition to the Wesleyan ideal of holiness, the IPHC benefited from a great stirring of the Holy Spirit that began at the opening of the 20th century. In January 1901, students at a small Bible college in Topeka, Kansas, began to speak in other tongues following their study of the book of Acts.

The influence of that experience reached the life of an African-American preacher named William Seymour. Blind in one eye and faced with the cultural obstacles of racism, Seymour went to Los Angeles, California, in 1906. Through his ministry, the Holy Spirit fell in Pentecostal power in April of that year. The sounds of “new tongues” spread around the globe. The revival grew and the services moved to a building on Azusa Street, near downtown Los Angeles. The ridicule of the media only served to advertise this unusual experience and bring hundreds more to the services. The word spread around the world through the remainder of 1906. The manifestations of spiritual power included victory over racial and gender discrimination. Many became missionaries of the gospel through the revival and believed that other tongues enabled them to share the gospel in the languages of the lost.

William J. Seymour (seated, second from right) with the leaders of the Azusa Street Mission in 1906. Also pictured: (standing, left to right) Phoebe Sargent, G.W. Evans, Jennie Evans Moore, Glenn A. Cook, Florence L. Crawford, Thomas Junk, Sister Prince; (seated, left to right) May Evans, Hiram W. Smith (holding Mildred Crawford), Seymour, and Clara Lum.

People in the Fire-Baptized Holiness Church and the Pentecostal Holiness Church of North Carolina read about the Los Angeles revival. In the fall of 1906, Gaston Barnabas (G.B.) Cashwell, a minister in the North Carolina church, decided to go to Los Angeles to see firsthand what was happening. After he arrived, he received the baptism in the Holy Spirit, spoke in other tongues, was healed of a health problem, and stayed several weeks preaching in the greater Los Angeles area. When he returned to his home in Dunn, North Carolina, in December 1906, he announced special services for New Year’s Eve.

Following Seymour’s pattern, Cashwell began services that exploded with Pentecostal power. People came from across eastern North Carolina, and blacks and whites worshiped together in these services. Many received the Pentecostal baptism of the Holy Spirit with the evidence of speaking in other tongues. Many experienced divine healing, and many responded to various forms of ministry. In February 1907, Cashwell began traveling to other areas. Over the next two years he led hundreds to experience Pentecost.

Through Cashwell’s ministry, the following denominations were directly or indirectly affected and became Pentecostal after the Acts 2 and Azusa Street model: the Pentecostal Holiness Church of North Carolina, the Fire-Baptized Holiness Church, the Pentecostal Free-Will Baptist Church, the Church of God (Cleveland, TN), the Church of God in Christ (Memphis, TN), and the Assemblies of God.5

A Spirit-Led Union

When representatives from these bodies met formally in Falcon, North Carolina, in the United States of America, the Holy Spirit wedded them through common theological understandings, opportunities of geographical proximity, and personal relationships. Through these elements, the Holy Spirit revealed to them the earliest glimpses of Christ’s purposes through the growing movement of IPHC Ministries. One hundred years ago the Pentecostal Holiness Church was limited to a few time zones; today the sun never sets on the IPHC global family.

The January 1911 organizational meeting in Falcon did not occur as a spontaneous event. For several years, leaders of these movements had been in spiritual relationship. In 1909, the North Carolina Holiness Church formed a committee of three to begin discussions with the Fire-Baptized group. In 1910, the Fire-Baptized, being the larger of the two groups, followed suit by appointing a committee of five. These eight men met in in Falcon in April 1910 to lay the necessary foundations for the impending merger.

They decided to call the new denomination by the name of the smaller group, The Pentecostal Holiness Church. They would elect a General Superintendent as leader, and they wrote a “Basis of Union” to contain their doctrine.

Momentum for the merger continued through the Christmas holidays of 1910. George Floyd (G. F.) Taylor was chosen to represent the Holiness Church of North Carolina; F. M. Britton, the assistant general overseer of the Fire- Baptized, was chosen to represent that group; and J. A. Culbreth of the Falcon Camp Meeting was selected as a third member by Taylor and Britton. They met in Taylor’s Falcon home over Christmas and ironed out the foundational polity of the denomination in a manual called the Discipline.

One of the interesting aspects of these meetings was that the general overseer of the Fire-Baptized, Rev. Joseph Hillery (J. H.) King, was not present. Responding to a prophetic word that he should travel the globe as a messenger of Pentecost, King had traveled to San Francisco in the summer of 1910 and left San Francisco for Asia on September 20, 1910. He would not return to the United States until August 1912.

Thus, King left his own organization in the hands of others as related to the merger with full confidence in their ability to make the right decisions. This action by the leader of the Fire-Baptized showed his confidence in F.M. Britton, as well as the depth of trust among the leaders of both movements.

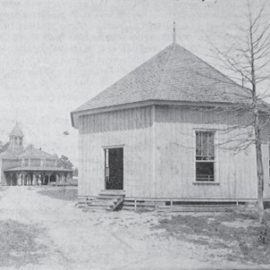

The meeting at the Octagon Tabernacle in Falcon began on Tuesday, January 31, 1911, at 9 a.m. Approximately 40 people gathered and elected A. H. Butler as chairman pro tem and J. A. Culbreth as secretary pro tem. Both men were from the PHC of North Carolina. While the North Carolina group was ready to adopt the new Discipline, the Fire-Baptized focused on a procedural question related to election of officers. Heated debate ensued and some were concerned that the effort to merge would flounder. But in the heat of the debate, Fire-Baptized lay delegate A. E. Robinson offered a motion adopting the Discipline verba et literatum.6 That motion passed 36-2 and in response, delegates began praising the Lord, hugging one another, and singing “The Old-Time Religion,” and “Blest Be the Tie That Binds.” In those moments of precious unity, they put aside organizational decorum and received an impromptu offering for one of their brethren who was ill.

The Octagon Tabernacle in Falcon, NC

The Spirit-anointed delegates moved forward with their business and elected Fire-Baptized minister S. D. Page as the first general superintendent of the newly formed Pentecostal Holiness Church. A. E. Robinson, the layman who had offered the motion, was elected as the first general secretary-treasurer. A. H. Butler was elected assistant general superintendent with responsibility for home missions and J. H. King, though absent, was elected as assistant general superintendent for foreign missions.

Several important factors stand out for us as we reflect on this event that occurred over one hundred years ago. First, the two groups had spent a decade building relationships and pursuing ministry opportunities together. Second, because the leaders knew one another, they had developed trust among themselves and a recognition of godly character and gifts. Third, though they faced tensions, there were anointed leaders who could speak words of wisdom and knowledge to bring needed breakthroughs. Fourth, laypeople had a significant voice and presence in the denomination and were recognized for their leadership and spiritual gifts. Fifth, the love offering for the sick brother affirmed care and generosity as a prominent feature among our early leaders. Sixth, the church was already sending missionaries outside the United States.

J. H. King

The Preface to the 1911 Constitution and General Rules of The Pentecostal Holiness Church set forth the missional framework of the IPHC. It begins with God’s orderly work in creation, God’s orderly purpose for Israel, and Christ’s calling of the twelve apostles and “the commandments concerning the Kingdom, ‘Go ye, therefore, and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost; teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you, and lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age’ (Matt.28:20).”

The Preface concludes with this charge:

The apostles went forth, preaching everywhere, and the people were converted and sanctified, forsook not the assembling of themselves together as the manner of some now, but formed the saved into local congregations, and called them churches, and ordained elders and deacons, and always left some one [sic] to look after the spiritual temporal interests of the Church. Let us humbly follow Christ, our great Leader, and take His word for our rule of faith and practice. Amen.

Thus, the mission of the IPHC began in God’s eternal purposes of redemption and reconciliation for the world. The recognition of Israel is important because it tied the church to the full counsel of God in both the Old and New Testaments. It affirmed the apostolic commission of Christ. Importantly, the Great Commission of Matthew 28:20 stands as the first official biblical text citation of the Pentecostal Holiness Church in its government policies. That citation continues to be true for us to this day!

Ultimately, the 1911 merger brought together about 2,000 Pentecostal Holiness members, primarily in North Carolina, Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Oklahoma, and Tennessee. Missionaries from the two movements had already gone to China, India, and Africa.

Today, the IPHC has works in 48 of the 50 states of the United States with over 200,000 members. Overseas, the IPHC ministers in one hundred nations with a membership of approximately 2 million.7 The sun never sets on the IPHC!